Why Water Won’t Infiltrate Hydrophobic Soils

Following heatwaves and droughts many farmers face challenges re-wetting dry, water repellant soils, to get them back to optimal moisture levels.

Heatwaves and droughts often leave farms, which may also be facing challenges with irrigation restrictions, with the challenge of trying to re-wet dry soils. Once soils become water-repellent, it can be a laborious task to get moisture levels back to optimal.

How does Soil become Water Repellent?

Soil repels water due to its hydrophobe content. Hydrophobes are organic molecules that repel water. They can be released in soils as a result of microorganism activity, organic matter, and decomposing plant tissue. Hydrophobes create a thin waxy coating around each soil particle, thus making the soil hydrophobic (water-repellent). The higher the soil hydrophobicity level, the lower the infiltration rate of water. Water molecules are bipolar and have strong cohesion forces: they attract molecules of the same kind. Their strong attraction to each other and their weak ability to bond with the waxy soil particles lead to the formation of droplets with a high contact angle. This high surface tension stops the water droplets from spreading over a large surface area. The likelihood of a soil being or becoming water-repellent is determined not only by the presence of hydrophobic material, but also soil texture (Hunt and Gilkes, 1992). Coarsely textured sandy soils that contain less than 5% clay are very susceptible to becoming water-repellent.

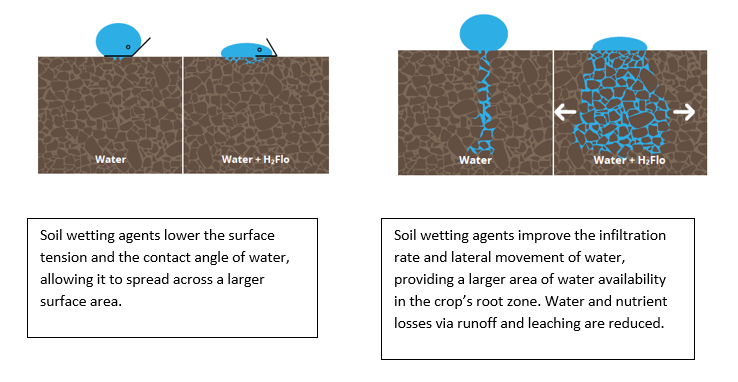

Graphic 1: Water in hydrophobic soils.

Applying extra irrigation in these situations will only lead to increased costs for water, labor, and pumping, and have little or no effect on improving the soil’s moisture level. Even minimal levels of water repellency can negatively impact water movement in soils, which in turn affects plant growth and development, which will lead to a reduction of the crop yield and the quality of the final produce.

How do Soil Wetting Agents Work?

Soil wetting agents are products based on surfactants, designed to improve water penetration and to allow better water distribution into the soil profile, both horizontally and vertically. When mixed with water, the active ingredients reduce the cohesion force and increase the adhesion force (the force attracting water molecules to other substances, i.e., soils) so the soil no longer repels water. https://youtu.be/n4GyBJg34dw Soil wetting agents also prevent water pooling on the soil surface by reducing the water surface tension. Put simply, surfactants are formed by a hydrophilic head and a hydrophobic tail. When mixed with water, the hydrophobic tail protrudes from the water surface, reducing its surface tension. A lower surface tension decreases the contact angle, allowing water to spread across a larger surface area. This reduces water losses via runoff, especially on modeled soils (e.g., vegetable beds, ridges formed after potato planting, or carrot sowing) and improves the water infiltration rate.

Graphic 2: Surfactant molecules break the surface tension of water when the water-repellent “tail” protrudes from the water surface.

When coping with hydrophobic soils, combining agrotechnical practices like claying and furrow-sowing with the latest soil wetting agents is an effective way to reduce soil hydrophobicity. Giving water the chance to penetrate more rapidly into the soil will reduce water wastage, and increase healthy root development. A healthy root system results in improved nutrient uptake and better plant establishment. Maximizing the use of irrigation water saves costs, and obtain yields at the optimum potential of the crop.

Reference

Sources quoted: Hunt, N. and Gilkes, B. (1992) Farm Monitoring Handbook.